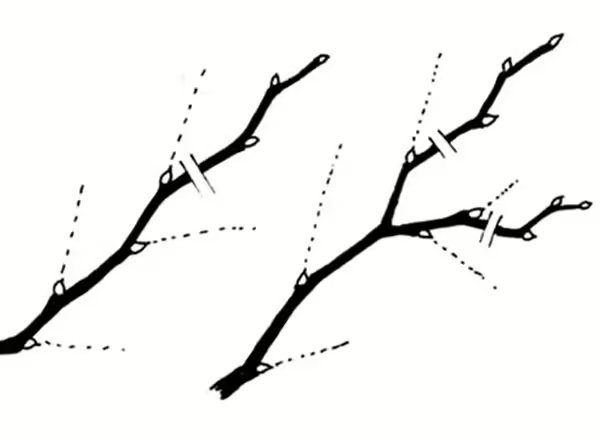

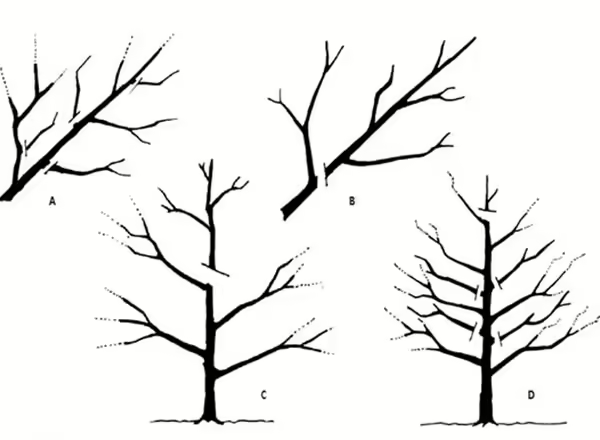

“Heading back” or “tipping” refers to cuts into the current season’s growth during the growing season and into the previous season’s growth during the dormant season. Such cuts are made to encourage the growth of lateral (side) branches. A general rule about heading- back cuts is that when 1-year-old branches are headed back during the dormant season, shoots will grow from lateral buds from the cut to about 10 inches below the cut. The general effect of heading-back pruning is a denser, compact type of growth (Figure N16).

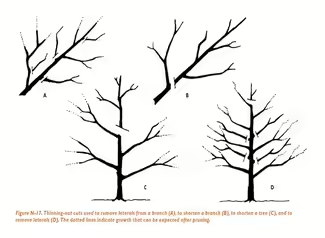

The vast majority of pruning cuts are classified as thinning-out cuts. They are used to shorten a branch or the trunk, remove a branch entirely, and reduce the number of laterals growing from a branch or the trunk. The general effect of thinning-out pruning is a more open, rangy type of growth (Figure N17).

Proper equipment is essential for successful pruning. For the home gardener these tools are hand pruning shears for small cuts up to 1⁄2 inch in diameter; lopping shears with 24 to 30 inch handles for cuts be- tween 1⁄2 and 1 inch in diameter; and a pruning saw for cuts over 1 inch. Pruning saws have teeth with a wide set to prevent binding by the living wood and fresh sawdust. Most pruning saws cut on the pull stroke to help avoid binding. Carpenters’ hand saws are de- signed for dry lumber, bind in fresh wood, and cut on the push stroke. Another useful tool, especially for taller trees, is the pole pruner, essentially a cutting head mounted on a long pole. Some pole pruners can cut through 11⁄2 inch branches located 12 to 16 feet above the operator.

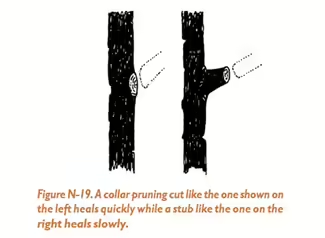

All pruning tools should be kept oiled and sharp to make clean, non jagged cuts. A clean wound heals more rapidly and smoothly.

The frequently heavy weight of fruits at harvest time requires a strong tree framework to prevent breakage. Branches with wide-angle crotches are stronger than those with narrow crotch angles. Main scaffold branches with strong crotches should be selected while the tree is small, especially with apple, peach, and nectarine trees. Strong crotches are desirable but not as critical with pear, cherry, plum, and apricot trees.

The various fruit trees differ in the manner in which they produce fruits. In order to intelligently prune fruit trees, as well as any other fruiting plants, these fruiting habits should be known, since they affect the type and extent of pruning.

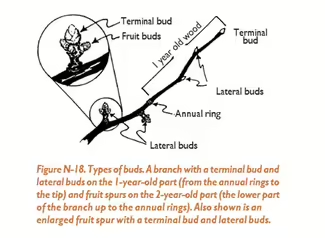

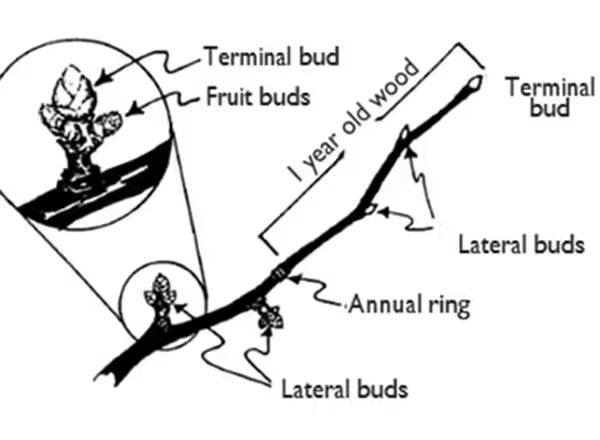

Fruits may be borne laterally (along the branch) or terminally (at the tip) on 1-year-old twigs or on fruit spurs produced on older wood. Fruit spurs are short, modified branches that grow very slowly (usually less than 1 inch per year) and usually bear fruits every other year (Figure N-18.). The amount and type of pruning are largely determined by the portion of the crops borne on buds in the various positions on the tree. Although exceptions occur, the following descriptions of fruiting habits are a reliable guide.

- Apples and pears produce most of their fruits terminally on spurs that are found on wood 2 years old and older. Individual spurs frequently live 15 or 20 years but their productive life is not over 8 to 10 years. In general, apple and pear trees need moderate pruning once they are trained and come into bearing.

Apricots, cherries, and plums produce most of their fruits laterally on spurs on wood 2 years old and older.

- Apricot spurs are usually not productive for more than 3 years so the pruning treatment should be designed to cause continual renewal of the fruit spur system. Sweet cherries bear entirely on spurs that carry numerous fruit buds. The spurs are productive for 10 to 12 years, so the sweet cherry needs less renewal wood than almost any other deciduous fruit tree.

- Sour cherries bear largely on spurs, but also on lateral buds on short 1-year twigs. Moderate renewal pruning to maintain an abundant spur system is desirable.

- European-type plums bear primarily on long, slender spurs that are frequently branched while Japanese-type plums bear, as a rule, on short thick spurs with a minor portion of the crop borne laterally on 1-year-old twigs. Japanese and hybrid type plums tend to set too many fruits; therefore, moderate to severe annual pruning is needed to reduce the number of fruit buds. European-type plums are less likely to over produce. Light annual pruning is suggested for them.

- Peaches and nectarines have identical fruiting habits, bearing their fruits almost entirely from lateral buds on 1-year-old twigs. Thus new fruiting wood must be produced each year. Probably no other fruit trees respond more to proper pruning and decline with neglect more than peaches and nectarines. Since new growth must be continually stimulated to maintain enough fruiting wood each year, peaches and nectarines should be pruned more heavily than most other fruit trees.