Title

County Level Renewable Energy

At the county level, state law requires that commercial solar and wind energy systems be an allowable use on land zoned as agricultural or industrial. Developers still need to go through a community’s permitting process.

Siting Commercial Wind and Solar Energy Conversion Systems

In January 2023, the Illinois legislature enacted Public Act 102-1123, which requires counties to allow commercial, utility-scale solar and wind energy conversion systems to be sited in areas zoned for agricultural or industrial use. The purpose of the legislation is to advance renewable energy throughout the state while also providing siting guidelines for commercial solar and wind energy conversion systems.

A county can have more lax requirements than called for in state law, but it cannot have more restrictive requirements.

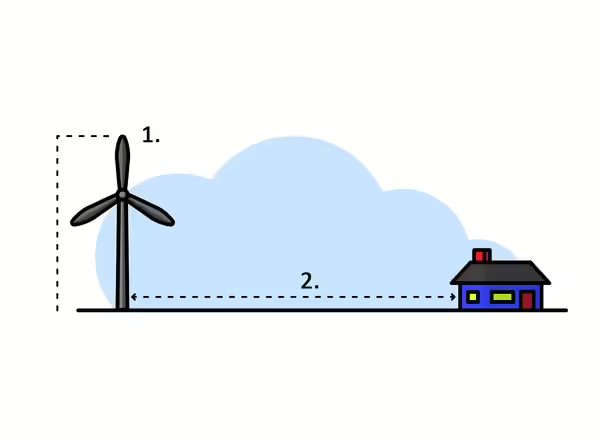

For example, (see illustration) the state law sets a maximum setback distance of 2.1 times the total blade tip height (1.) of a wind tower from the center of the turbine base to the nearest outside wall of a residence (2.) that is not located on land leased by the developer. A county could decide to have a lesser setback, but not a greater setback.

Other provisions covered by the state pertain to vegetative screening, fencing, and limiting shadow flicker.

Helpful Definitions

County Board

County Board refers to the governing body for counties in Illinois. These boards are elected by voters in each county and serve as both the legislative and executive branches of the county. They adopt ordinances (laws) and can direct the work of county departments.

Zoning Ordinance, District, or Board of Appeals

Zoning Ordinance refers to the laws adopted locally that govern land uses and aspects of site planning or design.

Zoning District refers to an area of a municipality or county that is subject to the zoning ordinance and has distinct, allowable land uses listed in said ordinance.

Zoning Board of Appeals refers to a board appointed by a county or city to hear cases related to zoning ordinances. The role of the zoning board of appeals differs depending on whether it has been established for a city or for a county. In counties, it is generally the zoning board of appeals that will hold public hearings on special use permits and other aspects of zoning regulations.

Building Ordinance or Permit

Building Ordinance refers to the laws adopted locally that govern standards of construction to ensure structural integrity. This type of ordinance is often referred to as a building code, and it can also include regulations to ensure new buildings or renovations are energy efficient.

Building Permit refers to a document granted by a local government stating that construction is allowed pursuant to the applicable zoning and building ordinances.

Special Use Permit

Special Use Permit, sometimes called a Conditional Use Permit, refers to a permit that is approved or denied after a public hearing by the local governing body, such as a City Council, Planning Commission, or a Zoning Board of Appeals. Special uses are those land uses that are difficult to account for in a community’s zoning ordinance but may become desirable or pertinent. They may be allowed in a particular zoning district provided that they meet certain standards of approval to protect health and safety, as well as the character of the surrounding area.

Understanding Commercial Renewable Energy and State Law

Find answers to some common questions related to commercial-scale renewable energy and Illinois legislation.

How does the legislation define commercial wind energy conversion systems?

Illinois defines commercial wind energy in terms of the project’s total nameplate generating capacity. Explore more about Wind Turbine Height and Energy Production. Each wind turbine installed for a project has a nameplate from the manufacturer that specifies how much energy that single wind turbine can produce if it runs continuously under perfect conditions.

If, when all of a project’s turbines are combined, a project will have 500 kilowatts (kW) or more of total nameplate generating capacity, then a county must allow it to be sited in accordance with Public Act 102-1123.

Understanding how kilowatts compare to megawatts is important in gaining perspective on how much power modern wind energy projects generate.

- One kilowatt (kW) is equal to .001 megawatts (MW)

- One megawatt (MW) is equal to 1,000 kilowatts (kW)

- Five hundred kilowatts (kW) is a half of one megawatt (MW)

It is typical in Illinois for commercial wind energy systems to have over 200 megawatts (MW) of nameplate generating capacity. This is due in part to advancements in how much power a single wind turbine can generate. As the rotor diameter, or blade length, on wind turbines has increased in size, so too has their energy-generating capacity.

The state’s threshold for what meets the definition of a commercial wind energy system is low enough that it will likely encompass most wind energy developments moving forward.

Find more information on Wind Energy.

How does the legislation define commercial solar energy conversion systems?

Unlike wind energy systems, the state legislation defines commercial solar energy systems based on their primary purpose, and this is because the definition is being reused from the Illinois property tax code.

Commercial solar energy systems are defined as an array that is ground installed, with the primary purpose of energy production being for wholesale or retail sale and not primarily for consumption on the property on which the array is constructed.

Wholesale or retail sale of energy production means that the energy produced by the solar array is being purchased by utilities so it can be used in the grid. This definition of commercial solar energy systems likely also applies to “community solar” projects, wherein individuals can buy shares of the electricity produced by a solar array within their electrical territory.

This means that ground-installed, or ground-mounted, solar arrays that provide energy just for a specific property, such as a residence, a business, or a municipal building, would not be considered commercial systems and would be subject to different siting guidelines than those in Public Act 102-1123.

The way the definition of commercial solar energy is currently written in the tax code also means that roof-mounted solar arrays would not be considered commercial solar energy systems.

To learn more about solar energy, including community solar, please see our page [INSERT LINK to solar-specific page] with helpful explanations and resources.

*Please note that if a solar project is inside of city limits, it is not subject to Public Act 102-1123, as this piece of legislation only applies to county jurisdictions, i.e. outside of city limits.

What if our county has an adopted zoning district map and zoning ordinance?

If your county established zoning districts and adopted a zoning ordinance prior to the enactment of Public Act 102-1123, then your local ordinance should be amended to be in conformance with state law. It can still be possible to include site planning requirements in your ordinance, but please consult with your legal counsel before adopting additional standards to ensure they do not conflict with state law.

What if our county does not have an adopted zoning district map or zoning ordinance?

If a county has not adopted a zoning district map or zoning ordinance, or otherwise adopted standards specific to commercial wind and solar energy systems, then that county is unable to place regulations on the development of solar or wind energy conversion systems because it does not have laws for developers to abide by in its jurisdiction.

What is the point of adopting a local zoning ordinance for commercial solar and wind development if the state has enacted its own requirements?

Beyond having the ability to review commercial solar and wind energy system proposals, having a local ordinance could allow a community to account for site planning that the state law does not. Site planning elements could include elements such as anti-climbing requirements, vegetative or screening requirements, or stormwater requirements. A local ordinance may also be able to include provisions for safety training that developers must provide to local fire departments.

A local ordinance can outline for the solar and wind developers what documents are required in order for an application to be considered complete by the appropriate board. This information can be beneficial for both the developers and the community, as it makes expectations clear from the beginning and ensures that adequate information will be provided for the board to review prior to voting on the project.

It is also important to have clear guidelines on what makes an application complete because of how Public Act 102-1123 is worded:

- The law states that the county must hold a public hearing within 45 days of the developer filing an application with the county.

- If a county does not have clear guidelines for what the application must include to be considered complete, discrepancies could arise as to when the 45-day clock begins.

Additionally, application materials become public domain unless otherwise noted by the applicant (e.g. archaeological reports are often considered confidential so as to not reveal sensitive information for areas that are not protected). By outlining what materials the county requires the developer to submit, local officials will have a complete set of information to share with the public, which promotes transparency.

What should county officials and the public expect at a public hearing?

Special use permits that are granted to commercial wind and solar energy systems go through a public hearing process wherein the developer, acting as the applicant, will present their project to a Zoning Board of Appeals or the full County Board, depending on how a county’s ordinance is written.

County staff, the applicant (most likely the project developer), and members of the public can provide testimony at these public hearings.

The board members base their decision on facts included in the application and presented during the public hearing(s). If the County Board has delegated the authority to the Zoning Board of Appeals to grant special use permits on its own, then the Zoning Board of Appeals will draw up “Findings of Fact” that details how they reached their decision and outlining how each standard of approval was or was not met.

Standards of approval are incorporated into the county’s ordinance and generally cover concerns such as health and safety, property values, and conformance with the surrounding area/land uses. For example, a wind developer submitting a plan for what roads it will use to reach the site or showing on a site plan where crews will park may meet a standard of approval to minimize traffic congestion (safety). Vegetative buffers between the ground-mounted solar arrays and neighboring properties may meet a standard of approval that others’ enjoyment of their own property is not diminished (conformance with surrounding land uses).

As previously mentioned for why adopting an ordinance for commercial solar and wind is important, application materials from the developer/applicant generally become public domain. Members of the public should be encouraged to review the application documents so they can prepare for the public meeting and provide relevant testimony if they wish to do so.

Public hearings follow rules of procedure so that business can be conducted in an orderly manner and so that the recording secretary can easily capture what is said and who said what.

What if our county is concerned about environmental impacts from commercial wind and solar development?

A county may choose to enact the provisions from Public Act 102-1123 for wind turbines and solar components to be set back a certain distance from protected lands as identified by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources or the Illinois Nature Preserves Commission.

The legislation defines “protected lands” as real property that is:

“(1) subject to a permanent conservation right consistent with the Real Property Conservation Rights Act; or

(2) registered or designated as a nature preserve, buffer, or land and water reserve under the Illinois Natural Areas Preservation Act.”

For commercial solar energy projects specifically, the state guidelines include a provision for vegetative management for native, pollinator plantings. A county may choose to adopt these provisions if it so chooses.

The county should ensure with the developer that the solar panels and racking are designed to accommodate the pollinator plantings, however. Depending on the seed mix, some plantings could grow beyond 18-inches high and end up shading the solar panels if the racking and solar panels are installed too low to the ground. This could result in the pollinator plantings either being mowed, thereby reducing their effectiveness in creating habitat, or being left as-is, which will reduce the solar project’s efficiency and output.

Research from federal agencies and others is ongoing on the effects on wildlife from utility-scale solar and wind energy systems. If your county is concerned about long-term impacts on wildlife, we encourage you to reach out to Illinois Extension staff regarding research on the topic or visit one of these online resources for information:

What if our county is concerned about damage to agricultural lands?

The Illinois Department of Agriculture (IDOA) has developed an Agricultural Impact Mitigation Agreement (AIMA), which is referenced in Public Act 102-1123 as the standards to which a county can hold developers for lessening damage to agricultural land, both during and after construction. The AIMA covers topsoil separation, decompaction, and drainage tile repairs, among other points of interest. The templates for the AIMA documentation are publicly available here.

An AIMA is required to be submitted to IDOA and the local County Board regardless of whether that county has adopted an ordinance pertaining to commercial solar and wind energy systems.

What happens when a commercial solar or wind energy system reaches the end of its life?

Commercial solar and wind energy systems generally have a lifespan of 20-30 years; however, systems could operate longer than that if they are repowered–meaning components are replaced or upgraded–and if the landowner continues the lease agreement with the solar or wind developer.

If a landowner and/or the developer do not wish to continue their lease agreement, then the solar or wind energy system is decommissioned and removed from the landscape. The state of Illinois requires commercial solar and wind developers to provide financial assurance to counties during the permitting phase. Financial assurances, such as surety bonds, demonstrate that the developer will have the means to pay for the removal of the project, as well as the restoration of the land.

For more information on what happens to solar and wind energy projects during and after their useful life, please visit our page on repowering and decommissioning.

What if I am installing a solar or wind energy system to power my farm operation?

When it comes to siting solar or wind energy systems for agricultural use, i.e. a solar array to power hog houses or provide electricity to outbuildings, then it is possible that your project would be considered agriculturally exempt from certain zoning requirements, provided that agricultural uses constitute the primary activities on the property. Please check with your county or municipality to see what requirements would apply.

University of Illinois Extension cannot provide legal advice on interpreting Public Act 102-1123, and the information contained on our webpage is meant only as a resource.