A major component of planning for renewable energy projects is understanding where it may be located, or sited, in a community and how that location may be perceived by the public. This is true of any development project that may change the aesthetics of an area or be unfamiliar.

Zoning ordinances are the laws that cities and counties implement to regulate how land is used and where different types of development are located. Beyond articulating where developments can go, these ordinances can also set requirements for how a site is designed or planned. For instance, regulating setbacks for how far off of property lines structures or other components (like a ground-mounted solar array) must be. Another example of site design regulated by an ordinance is whether any fencing or vegetation is required to help screen certain uses from the road or residential properties.

Planning for renewable energy projects, whether large or small, requires an understanding of how ordinances can impact the project and what the benefits to a community or region may be if renewable energy development moves forward.

In the state of Illinois, rural counties that are less populous may elect to adopt ordinances that solely focus on commercial wind and solar development, without adopting zoning ordinances more broadly. This could be advantageous in the short term. More information on this can be found at the bottom of this page.

Helpful Definitions

Distributed Energy Generation, Utility-Scale Energy Generation

Distributed Energy Generation refers to when electricity is generated at or near a site where it will be used. The most common example of this is a solar array that provides electricity directly to a structure, whether it be a residence or business.

Utility-Scale Energy Generation, or centralized generation, refers to large-scale electricity generation, typical of nuclear or natural gas power plants, wherein the electricity that is produced is transmitted into the electric grid for use off-site. Large wind farms and solar arrays also operate as utility-scale energy generators.

Zoning Ordinance, District, or Board of Appeals

Zoning Ordinance refers to the laws adopted locally that govern land uses and aspects of site planning or design.

Zoning District refers to an area of a municipality or county that is subject to the zoning ordinance and has distinct, allowable land uses listed in said ordinance.

Zoning Board of Appeals refers to a board appointed by a county or city to hear cases related to zoning ordinances. The role of the zoning board of appeals differs depending on whether it has been established for a city or for a county. In counties, it is generally the zoning board of appeals that will hold public hearings on special use permits and other aspects of zoning regulations.

Building Ordinance or Building Permit

Building Ordinance refers to the laws adopted locally that govern standards of construction to ensure structural integrity. This type of ordinance is often referred to as a building code, and it can also include regulations to ensure new buildings or renovations are energy efficient.

Building Permit refers to a document granted by a local government stating that construction is allowed pursuant to the applicable zoning and building ordinances.

Special Use Permit

Special Use Permit, sometimes called a Conditional Use Permit, refers to a permit that is approved or denied after a public hearing by the local governing body, such as a City Council, Planning Commission, or a Zoning Board of Appeals. Special uses are those land uses that are difficult to account for in a community’s zoning ordinance but may become desirable or pertinent. They may be allowed in a particular zoning district provided that they meet certain standards of approval to protect health and safety, as well as the character of the surrounding area.

Planning Commission

Planning Commission refers to a commission that may be appointed by a mayor or city council to review and vote on matters related to the zoning ordinance of a municipality, including special-use permits.

Are zoning ordinances related to zoning districts?

Yes, they are! Zoning ordinances are the laws adopted by a municipality or county that govern allowable land uses within specific zoning districts. Zoning ordinances correspond with a zoning district map, which shows how a county or municipality has divided its jurisdiction into areas with distinct, allowable land uses.

It is important to remember that zoning ordinances can also include regulations for site planning, such as stormwater requirements, regulations to reduce light pollution, or the number of allowable parking spaces, to name a few. The number of site planning requirements and their stringency may differ depending on the zoning district.

As you can probably already tell, zoning ordinances and zoning districts are intertwined to such a degree, that if you are talking about one, you are also talking about the other. Zoning districts will be listed in a city or county’s zoning ordinance and shown on a zoning district map so that the public has a clear understanding of what land uses are allowed where.

Why do communities adopt zoning ordinances?

Zoning for land use came from a need to protect public health. As urban centers grew during the early 20th century and had an influx of population, it became abundantly clear that planned development was needed to prevent outbreaks of disease due to issues between wastewater and overcrowded housing units. Other goals from early planning initiatives included improving transportation and preserving open space, including public lands. The American Planning Association has a digital timeline of planning and zoning for those interested in the history.

Communities continue to adopt zoning ordinances and zoning districts in order to protect the health, safety, and general welfare of their residents. Perusing the list below of typical zoning districts, you may start to see a connection between designating specific land uses and the health and well-being of the people who live and work in a community. For instance, commercial or manufacturing zoning districts are kept distinct from residential zoning districts, where the primary land use is for homes.

Example Zoning Districts

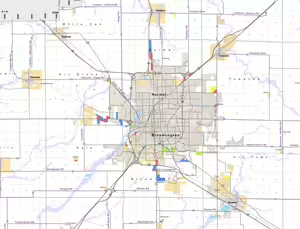

In this example zoning district map for McLean County, note that the agricultural zoning district is the largest district. Commercial and manufacturing districts are clustered close to city limits, possibly due to existing infrastructure and compatibility with the surrounding area. The county’s zoning jurisdiction does not extend into city limits. Find more information on separate zoning jurisdictions for counties and municipalities below.

Energy Planning Counties Energy Planning Municipalities

Agricultural

- Permitted uses often include commercial and small-scale farming, horse stables, grain elevators, and historic farmsteads.

- Special permitted uses can include industrial or commercial development that need large tracts of land, such as gravel mining and wind or solar farms.

Residential

- Permitted uses include single-family and/or multifamily dwellings.

- Other permitted uses may include in-home daycare centers, parks, or home businesses.

Commercial

- Permitted uses broadly encompass retail or wholesale operations and the service industry, such as event venues and restaurants.

- Commercial districts may include light manufacturing or warehousing where the risk of environmental contamination or other nuisances is low.

Industrial

- Permitted uses include industrial operations that may create nuisances due to emissions of dust, noise, and/or odor.

- May carry a risk of environmental contamination if spills or other accidents occur.

- Examples of permitted uses include cement manufacturing, petroleum processing, or slaughterhouses.

Conservation

- Permitted uses are extremely limited and generally allow public parks or preservation of open space.

- May be applied to mapped floodplain or other natural resources that a community chooses to protect.

Zoning Ordinances and Community Goals

Zoning ordinances can be a means for a community to achieve its goals, rather than simply a way to say “no” to proposals. Zoning ordinances are more than regulations; they can help communities achieve their vision by ensuring orderly development and holding developers accountable to that vision.

Ordinances are laws, meaning they have “teeth” for enforcement if a developer violates the ordinance. If a county or municipality has adopted a zoning district map, you will likely find it on their website, as zoning district maps are public information.

Many communities and/or regions will adopt comprehensive plans that outline their vision for development. Zoning ordinances can and should support a community’s comprehensive plan.

Comprehensive plans are a long-term blueprint for what a community wishes to achieve, or how they want to develop over the course of many years, generally 10 to 20 years. A comprehensive plan may have goals and objectives, categorizing what they want to achieve economically or culturally. Learn more in the Local Comprehensive Plan publication from the American Planning Association.

For example, a community may set a goal of reducing local greenhouse gas emissions. An objective may be to convert all municipal buildings and public community centers to renewable energy. Another objective may be to install electric vehicle charging stations around the community. In this scenario, zoning ordinances can ensure that renewable energy sources are explicitly allowed in a multitude of zoning districts or that overlay districts can be used to encourage certain types of economic development near vehicle charging stations.

Zoning ordinances can also include incentives, whereby some requirements might be loosened in exchange for the development providing a public benefit. Sometimes this is called “incentive zoning” and can be used to support multiple goals of a community.

For example, in exchange for avoiding natural resources, such as wooded areas and stream buffers, when platting a subdivision, a developer may be allowed smaller lot sizes, thereby achieving a similar number of housing units and a similar profit. This type of incentive can support the goal of natural resource preservation while maintaining a community’s aim for more housing options.

Permitting and Public Hearings

In Illinois, counties and municipalities have the authority to establish zoning districts and zoning ordinances under Chapters 55 and 65, respectively, of the Illinois Compiled Statutes. However, these same chapters also include state-regulated provisions for certain land uses.

Of interest for energy planning at the county level are the state’s requirements that counties allow commercial (utility-scale) solar and wind energy systems on land zoned for agricultural or industrial use. If a county has not adopted zoning districts, then utility-scale renewable energy projects must simply be permitted in accordance with state law and the permitting process the county has in place for other development projects.

Despite the state’s requirements, developers still need to go through a community’s permitting process. Even though a particular land use may be allowed in a community, either through their own established zoning districts or due to state law, this does not mean that individuals or developers can just begin construction without permits or oversight.

Special Use Permits

When it comes to utility-scale renewable energy projects, most communities will have a “special use” permitting process that includes at least one public hearing. Special uses are those land uses that are difficult to account for in a community’s zoning ordinance but nevertheless may occasionally become desirable or pertinent.

Special uses may be allowed in a particular zoning district provided that they meet certain standards of approval to protect health and safety, as well as the character of the surrounding area. Examples of special uses could include mining, astronomical observatories, private campgrounds, electrical substations, and solar or wind energy projects.

The developer of a solar or wind energy project will submit an application to the county or municipality with site plans and information about the project. This application begins the permitting and public hearing process.

Approving or Denying Permits at Public Hearings

Special use permits are not approved or denied in as simple a fashion as regular building permits. They go through a public hearing process that is, as the name implies, open to the public.

More populous counties and municipalities may have professional planning staff who review applications and development plans for conformance with an adopted zoning ordinance. These staff then make recommendations to the local government’s boards and commissions holding the public hearing(s).

Rural, less populous counties and municipalities often do not have professional planning staff and may rely instead on citizen volunteers who make up planning commissions or a city or county clerk to review the applications prior to public hearing(s).

In counties, if a Zoning Board of Appeals has been appointed, then they will hold a public hearing on the special use permit. In cities, the Planning Commission will hold a public hearing on the special use permit. In general, public hearings will include:

- A recording secretary taking minutes to create a record of what is said

- The applicant presenting their plans

- The board or commission asking the applicant questions

- Members of the public providing testimony at the hearing

- Members of the public are required to identify themselves, meaning that anonymous comments are not allowed

- The board or commission giving the applicant time to respond to testimony

- The board or commission deliberating and taking a vote on whether the special use permit should be approved or denied

- If the board or commission is unable to reach a consensus or feels they need more time to review documents, they may vote to table their decision and schedule an additional public hearing at a future date.

Find more information on public hearings on the Energy Siting for Counties page.

Steps for Special Use Permitting

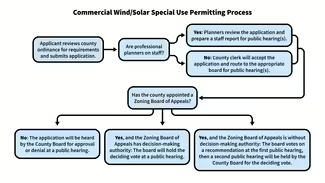

This flowchart explains the special use permitting process at the county level. While special use permitting at the municipal level is very similar, it is possible that there could be additional steps that are left up to a Planning Commission’s discretion. Reach out to your local city clerk if you have questions about how their process works.

Example Steps

- Applicant reviews the county ordinance for requirements and submits the application.

- The application is reviewed.

- If professional planners are on staff, they will review the applications and prepare a staff report for public hearings.

- If professional planners are not on staff, the county clerk will accept the application and route it to the appropriate board for public hearings.

- Has the county appointed a Zoning Board of Appeals?

- No. The application will be heard by the County Board for approval or denial at a public hearing.

- Yes, and the Zoning Board of Appeals has decision-making authority. The board will hold the deciding vote at a public hearing.

- Yes, and the Zoning Board of Appeals is without decision-making authority. The board votes on a recommendation at the first public hearing, then a second public hearing will be held by the County Board for the deciding vote.

Click on the image below to expand it. Illustration by University of Illinois Extension, Ben Arthur.

Can a county adopt an ordinance for utility-scale solar and wind without adopting an entire zoning ordinance or zoning district map?

Yes, this is certainly possible and is common in Illinois in rural counties. A land use ordinance just for commercial, utility-scale solar or wind projects can still outline what site planning is required from the developer and what documents must be submitted with an application in order for a public hearing to be scheduled. These types of ordinances can be a short-term measure to address renewable energy’s expansion on the rural landscape, but if a county wishes to be more engaged with planning for a renewable energy future, then thinking about a comprehensive plan–perhaps joining with other counties at a regional scale–could establish long-term goals and objectives for energy generation and conservation. Completing a comprehensive plan could lead to establishing zoning districts and a zoning ordinance to support what the county wants to achieve.