URBANA, Ill. — Nanoplastics are everywhere. These fragments are so tiny they can accumulate on bacteria and be taken up by plant roots; they’re in our food, our water, and our bodies. Scientists don’t know the full extent of their impacts on our health, but new research from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign food scientists suggests certain nanoplastics may make foodborne pathogens more virulent.

“Other studies have evaluated the interaction of nanoplastics and bacteria, but so far, ours is the first to look at the impacts of microplastics and nanoplastics on human pathogenic bacteria. We focused on one of the key pathogens implicated in outbreaks of foodborne illness — E. coli O157:H7,” said senior study author Pratik Banerjee, associate professor in the Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition and an Illinois Extension Specialist; both units are part of the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences at Illinois.

Banerjee’s team found that nanoplastics with positively charged surfaces were more likely to cause physiological stress in E. coli O157:H7. Just as a stressed dog is more likely to bite, the stressed bacteria became more virulent, pumping out more Shiga-like toxin, the chemical that causes illness in humans.

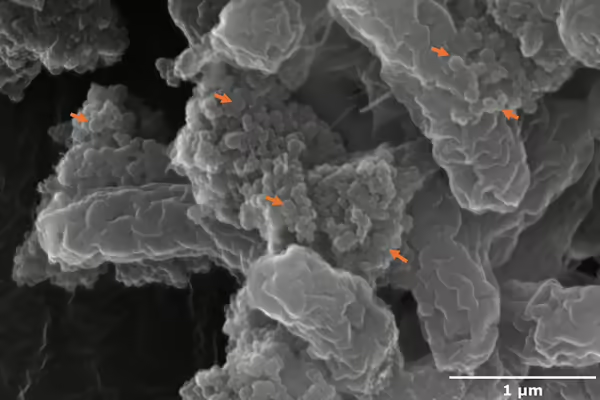

The researchers expected positively charged nanoplastics to impact E. coli because the bacteria’s surface carries a negative charge. To test their opposites-attract hypothesis, they created nanoplastics from polystyrene — the material in those ubiquitous white clamshell-style takeout boxes — and applied positive, neutral, or negative charges before introducing the particles to E. coli either free-floating in solution or in biofilms.

“We started with the surface charge. Plastics have an enormous ability to adsorb chemicals. Each chemical has a different effect on surface charge, based on how much chemical is adsorbed and on what kind of plastic,” Banerjee said. “We didn’t look at the effects of the chemicals themselves in this paper — that’s our next study — but this is the first step in understanding how the surface charge of plastics impacts pathogenic E. coli response.”

The bacteria exposed to positively charged nanoplastics showed stress in multiple ways, not just by producing more Shiga-like toxin. They also took longer to multiply when free-floating and congregated into biofilms more slowly. However, growth eventually rebounded.

Read the full article from the College of ACES.

University of Illinois Extension develops educational programs, extends knowledge, and builds partnerships to support people, communities, and their environments as part of the state's land-grant institution. Extension serves as the leading public outreach effort for University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences in all 102 Illinois counties through a network of 27 multi-county units and over 700 staff statewide. Extension’s mission is responsive to eight strategic priorities — community, economy, environment, food and agriculture, health, partnerships, technology and discovery, and workforce excellence — that are served through six program areas — 4-H youth development, agriculture and agribusiness, community and economic development, family and consumer science, integrated health disparities, and natural resources, environment, and energy.