Do you know where your drinking water comes from? If you are like most people, the answer is no.

While the City of Chicago and many of its surrounding communities access water from Lake Michigan, the rest of northeast Illinois relies primarily on groundwater aquifers for its drinking water. Groundwater aquifers provide a wide range of opportunities for drinking water, as well as a variety of challenges.

Where does our water come from?

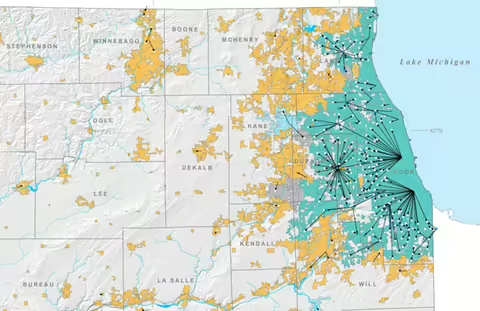

In northeastern Illinois, McHenry, Boone, Winnebago, and DeKalb counties are 100% dependent on groundwater aquifers for their drinking water. While most of Kane County relies primarily on groundwater, its two largest cities, Elgin and Aurora, draw from the Fox River for much of their water supply. However, due in part to extended periods of drought that can lower water levels and degrade water quality in the river, those cities are now increasingly relying on groundwater.

Figure 1: A map depicting sources of drinking water in Northeast Illinois. The turquoise color represents water supplied by Lake Michigan. Brown represents drinking water supplied by groundwater. Source: Illinois State Water Survey Map Series 2017-01

How are groundwater aquifers structured?

Groundwater aquifers are layers of porous sediment or rock that can store and transmit water underground. In northeast Illinois, aquifers are not underground lakes or rivers. Instead, the water flows in the pore spaces between the grains of sand and gravel, or in the fractures of hard bedrock. Groundwater is replenished when rainfall or snowmelt soaks into the soil and is filtered as it percolates downward, filling in the pores and cracks of the soil and rock below ground. The size of the aquifer and how easily water can flow through it help to dictate the aquifer’s ability to provide drinking water through wells. Private wells can be drilled to provide individual homes with water, while larger diameter high-capacity wells can be drilled to provide water to communities.

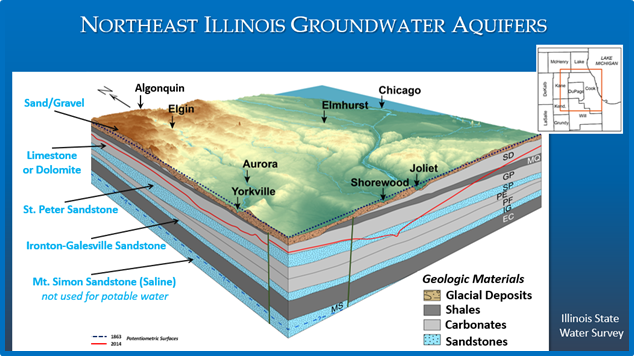

Large areas of northeast Illinois have a unique geology that provides access to several forms of groundwater aquifers that are not found in many other parts of the state. These geologic formations include:

- Sand and gravel aquifers;

- Shallow bedrock (limestone or dolomite) aquifers; and

- Deep bedrock (sandstone) aquifers.

Sand and gravel aquifers

The uppermost sand and gravel aquifers formed from glaciation during the last ice age, the Wisconsin glacial episode, which ended around 12,000 years ago. This glacial geology can include large areas of highly permeable sand and gravel capable of filtering and storing large volumes of water. These sand and gravel aquifers are the primary source of water for residents on private wells and for many cities throughout the region. Most wells in the sand and gravel aquifers are between 50 to 300 feet deep.

Figure 2: A map depicting the geology and groundwater aquifers in northeast Illinois. Source: Adapted from Illinois State Water Survey Contract Report 2015-02.

The sand and gravel aquifers are not a continuous layer across the region. Instead, they are typically large pockets of sand and gravel separated by glacial till that is usually composed of less permeable silt or clay. These aquifers can be identified as “unconfined” or “confined” aquifers. Unconfined aquifers are open to the land surface above (at atmospheric pressure), so rainfall is able to percolate rather rapidly through the soil. Confined aquifers, on the other hand, are sandwiched above and below by beds of less permeable or impermeable “confining” layers. While unconfined aquifers can be more resilient to overuse because they recharge more rapidly by rainfall, they are more susceptible to pollution because pollutants can also percolate more quickly. In fact, large areas of sand and gravel aquifers throughout northeast Illinois have been polluted and can no longer be used for drinking water. Depending on the thickness of the less permeable “confining” material covering them (e.g., clay), confined aquifers can have a higher level of protection from pollution but can also be much more susceptible to drawdown of water levels because of the slow recharge rate.

Shallow bedrock aquifers

Below the sand and gravel is a thick layer of shallow bedrock composed of limestone or dolomite that formed about 400 million years ago, when Illinois was covered by an inland sea. Although the bedrock is not porous like sand and gravel, it can hold vast amounts of groundwater in its cracks and fissures. However, to function as an aquifer, the bedrock must be properly positioned to capture water that percolates through the sediments above. The cracks and fissures must also be aligned to allow water to flow readily through the bedrock. Because conditions have to be so perfectly aligned, shallow bedrock wells are usually used to supply smaller volumes of drinking water for private wells, or smaller municipalities. Wells in the shallow limestone/dolomite bedrock are commonly between 100 to 500 feet deep.

Deep bedrock aquifers

Our deepest aquifers are composed of three thick layers of sandstone that formed around 460 to 525 million years ago during periods when shallow seas covered much of Illinois and its surrounding states. Although the St. Peter sandstone aquifer is the shallowest of these aquifers, it is not widely used for drinking water because it has largely been desaturated and consists of a soft rock that easily breaks apart and can destroy a well's pump. At around 3,000 feet, the Mount Simon is the deepest aquifer, and it is not used for drinking water because its water quality is too brackish (brine).

The primary deep bedrock aquifer used in Northeast Illinois is the Ironton-Galesville aquifer, and it provides large volumes of drinking water for many municipalities and industries across many states. However, because it is covered by thick layers of impermeable rock, recharge to the Ironton-Galesville aquifer occurs far away, so it is not a renewable water source like the sand and gravel or shallow bedrock aquifers. In fact, so much water has been pumped from the Ironton-Galesville aquifer that some municipalities are running out of water and having to find alternate water sources.

The Importance of groundwater

It is important to remember that our groundwater is deeply interconnected with the natural resources around us. Groundwater provides a baseflow of cool, clean water to our lakes, rivers, streams, and wetlands. How we develop and manage the land around us has a direct impact on our water resources, which in turn directly affect the wildlife and people that depend on the water. Unfortunately, very few people consider the impacts on water when they make land use decisions.

While northeast Illinois has abundant water resources relative to much of the state, we are still subject to the same limitations as those around the world who are facing challenges to their water supply. If we use more water than is naturally recharged by rainfall, then our water tables drop. If we pollute our groundwater, it is no longer available for our use. These may seem like simple concepts to follow, but rarely do people act to protect their water until there is a problem. Fortunately, there are people working at the state, county, and local levels to help the public and decision-makers understand the challenges and opportunities before it’s too late.

This blog article was written by Scott Kuykendall, Water Resources Specialist, McHenry County Planning and Development.

Resources to learn more

- ILWater – Illinois State Geological Survey interactive map of water well locations

- McHenry County Water Resources Division

- University of Illinois Extension Watershed Stewards program

- Illinois Groundwork - community green stormwater infrastructure resources

Thank you for reading!

Everyday Environment is a series of blogs, podcasts, webinars and videos on exploring the intricate web of connections that tie us to the natural world. Want to listen to us chat about this topic? Check out the podcast episode on this topic to hear more from the Everyday Environment team about groundwater resources.

Listen to the Podcast Sign Up for Everyday Environment Newsletter