When temperatures start getting cold in late fall, it's time to make those last-minute preparations that help your bees have the best chance of surviving the winter.

Check for Varroa mites

This is your last chance to treat for Varroa mites. In the late fall, your Varroa mite sampling should show less than 1 mite per 100 bees, otherwise, you need to treat. A very useful tool for determining the best strategy for managing Varroa mites is the Honey Bee Health Coalition’s (HBHC) Varroa Management Decision Tool. Many Varroa mite treatment options are temperature-dependent, so read and follow the label recommendations.

For more guidance on the most current mite management strategies, check out the HBHC Tools for Varroa Management.

Feeding bees for winter

Have you checked to make sure your bees have enough food stored to survive the long winter? Our hives should have at least 90 pounds of honey to provide the bees with enough food to make it through the winter. If you are wondering what 90 pounds of honey looks like, it equals a full deep hive box or 2 medium supers full of honey. Bees can be fed sugar syrup up until the temperature falls below 50°F. This sugar syrup should be fed at a 2:1 ratio of sugar to water at this time of the year.

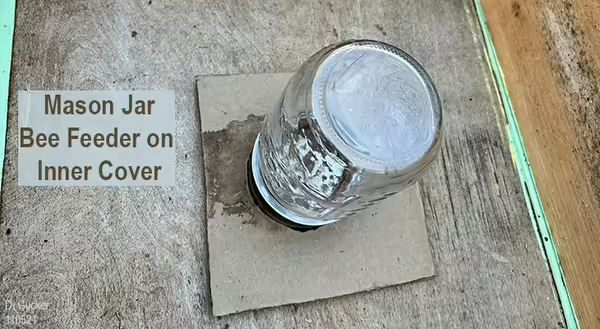

I feed my bees in late fall or early winter with a mason jar syrup feeder placed over the hole in the inner cover and then place an empty hive body on top with an outer cover. This allows the bees to feed without leaving the warm hive on cool or cloudy fall days.

During your hive inspections in late fall or winter, if you see your bees at the hole in the inner cover, then they are running out of food. Feed them dry food when temperatures are below 50°F. For winter feeding, read “Winter Feeding of Your Bees”.

Hive ventilation

Besides starvation and Varroa mites, another cause of winter bee mortality is condensation inside the hive. This occurs when moisture from the respiration of the bees and damp weather conditions cause moisture to condense on the inside of the inner cover. This condensation drips down on the bees in their winter cluster and chills them. Also, a moist hive is a favorable environment for disease organisms. Always provide ventilation for the hive at the top and bottom. Bees can survive the cold, but they do not tolerate high humidity levels. Tilt the hive slightly toward the front to allow any condensation water to drain out.

Winter hive location

Hive location in the winter is very important. Are the hives off the ground in a dry, sunny, sheltered location? A sunny, sheltered location out of the winter winds can be several degrees warmer than a similar location that is shaded or in the wind. Locate the hive entrance away from the prevailing winter wind direction to reduce drafts in the hive.

- Hives can be wrapped to reduce the wind blowing through cracks between the hive bodies, but do not close the top and bottom entrances. The hive must have bottom-to-top ventilation to keep humidity levels low in the hive.

- Is the outer cover weighted down to prevent it from blowing off in strong winter storms?

- Have you installed a mice or small rodent guard in the lower hive entrance? These can be purchased, or you make one from large mesh wire screening (3/8 inch square).

According to a survey of the Bee Informed Partnership, the two leading causes of bee colony winter mortality are weak bee colonies and starvation. With some fall preparation and a good year-round Varroa mite management program, you will greatly improve the odds of your bees surviving the winter.