There are just some native plants you just don’t want to cultivate near well-traveled paths, and most especially if you have a dog. I ’m talking about native plants that have developed a seed dispersal method that involves hitching a ride on any animal passing by. Just a few that I regularly encounter include begger-ticks (Bidens sp.), sandbur (Cenchrus longispinus), stick-tight (Desmodium sp.), snakeroots (Sanicula sp.) and stickseed (Hackelia virgiianum). It seems no matter how diligent I think I am at rogueing “sticky seed” plants out of my planting beds and along paths, never a year goes by that I don’t encounter a missed plant so fully that I actually consider just throwing away my burr-encrusted socks, shoelaces and pants…and whether to just shave my head and the dog too.

This year seems to be no exception. Just recently, I was bending down to take of photo of American lopseed (Phryma leptostachya), only to make an unfortunate contact with a Canadian black snakeroot (S. canadensis) growing inconspicuously nearby; resulting in a headful of burrs. A few days later and a little bit further down the path, I was examining a plant of unknown origin, only to realize it was a stickseed plant. I remembered keeping it as a rosette of leaves last fall because I wasn’t sure what it was. Though not related to Canadian black snakeroot, the outer surface of its tiny round fruits are similarly covered with hooked prickles and both are biennials tending to favor shadier conditions. This is the first time though I have been lucky enough to identify a “sticky-seed” plant from its bloom, rather than its burrs in my hair, clothes and all over the dog.

This spring I renewed a golden privet (Ligustrum x vicaryi) to the ground and it has been interesting to see what plants have emerged since exposing the ground under the shrub to sunlight. This rather large shrub marks the end of my driveway and has always been a favorite roost for the local songbirds, so they have had many years to litter the ground underneath with seeds through their droppings and seed waste. Shortly after cutting the shrub back and volunteer plants started to emerge, I used the iNaturalist app to help identify unknown plants and rogue-out any I deemed not worthy of keeping. One I kept was white vervain (Verbena urticifolia) for its worth as a pollinizer. White vervain can grow well over five feet, and relative to the size of the plant, the inflorescence is rather inconspicuous. Even though the individual florets are tiny, the various bees and flower flies seem to have no problem locating them. White vervain has a reputation of being somewhat weedy, but if it behaves itself, it will be a welcome addition to my jungle.

One of the challenges for any gardener, is incorporating season-long bloom using as many quality nectar and pollen plants as possible, not only for the obvious reason…pollinators, but also for contrast against the otherwise “green” of summer. As my garden transitions through the growing season, I am always amazed at the “changing of the flower guard,” so to speak. Gone are the iris, peonies and false indigo, only to be replaced by daylilies, bee balm and coneflowers, and yet to be replaced by asters and chrysanthemums. Variegation and other forms of leaf color modification are also another option for giving contrast to the garden. Plantain lilies (Hosta sp.), coral bells (Heuchera sp.), Siberian bugloss (Brunnera sp.), and lungworts (Pulmonaria sp.) are just some of the plant species with a wide range of cultivar selections for extending the garden palette with just their leaves alone.

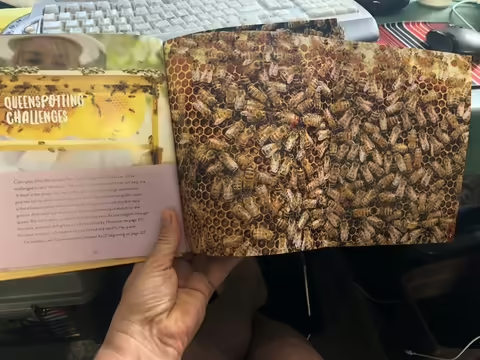

I love reading about the related topics of gardening when I can’t actually be out gardening. One book I thoroughly enjoyed recently was “QueenSpotting” by Hilary Kearney, published in 2019. As the title implies, this book focuses on the queen bee, the heart of a honeybee hive. In addition to the very enjoyable and informative text are 48 fold-out queen-spotting challenges interspersed throughout, which become progressively more challenging. If you enjoy challenges like “Where’s Waldo?,” you will really become immersed in finding the queen within a sea of bees. I still have a few of the tougher challenges where she still eludes me, but I refuse to get a clue from the answer key provided at the end of the book, but it’s still nice in a time of defeat. Great for kids and adults alike; beekeeping amateurs or professionals; this is a book for all.