About 6:30 p.m. on August 9, I started getting pictures of ominous storms from my colleague Peggy Doty who lives in northern Illinois. While we were sitting with a nice evening sky in central Illinois, the northern part of the state was experiencing multiple supercell storms and tornadoes.

I’ve discussed supercells in other posts, but I was curious about the mechanisms that caused this particular formation of supercells. So, I contacted Chris Miller at the National Weather Service office in Lincoln, who forwarded my questions to the Chicago office.

Here was the response from Science and Operations Officer Kevin Donofrio:

When forecasters assess the type of storms that we expect on a given day, also known as the "mode" of storms, we often assess both instability and wind shear. Instability is often related to the degree of warm, moist air near the ground compared with colder air aloft. The greater this difference, the more fuel for storms and faster rising motion and thus potential thunderstorms.

But not every thunderstorm becomes a supercell. A supercell is a rotating thunderstorm. Therefore, we need to assess a parameter called wind shear, which is the change of wind speed and direction with height. The greater the wind shear, the more likely to get a supercell thunderstorm. This is for several reasons: a thunderstorm with sufficient wind shear allows the warm, moist air rising in the thunderstorm (that provides the "fuel" for the storm) to remain separated from the rain-cooled air that sinks in a storm. The longer the storm lasts, that storm can be acted upon by the changing winds with speed and direction and be able to begin rotating. Once you have a rotating thunderstorm – you have a supercell!

There normally needs to be some mechanism which causes/encourages air to rise. A dry line is one case. In the midwest, often there is another frontal boundary either a cold front/warm front, or intersection of the two. Usually, on either side of the front (which are two different air masses colliding), winds are often coming from different directions. Sometimes it is more subtle, like a simple wind shift from a lake breeze boundary. These differences lead to winds colliding and the air being forced to rise, but the difference in wind direction is also an initial source of rotating air.

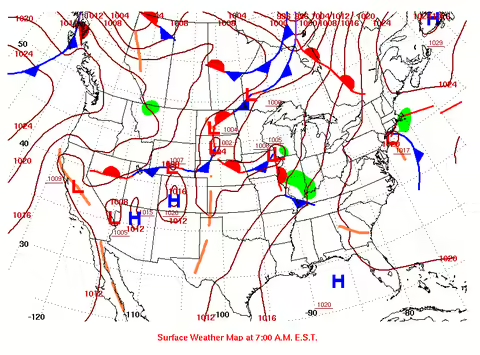

If you look at the surface weather map for the morning of August 9, you can see a warm and cold front intersecting in northern Illinois. This would have been moving through the area during the day.

MEET THE AUTHOR

Duane Friend is an energy and environmental stewardship educator with University of Illinois Extension, serving the organization in many roles since 1993. Duane provides information and educational programs to adult and youth audiences in the areas of soil quality, weather and climate, energy conservation, and disaster preparedness. These programs provide practical solutions for families, farms, and communities. He assists families in creating a household emergency plan, farmers with the implementation of soil management and conservation practices, and local government officials and business owners with energy conservation techniques.

ABOUT THE BLOG

All About Weather is a blog that explores the environment, climate, and weather topics for Illinois. Get in-depth information about things your weather app doesn't cover from summer droughts to shifting weather patterns.