With climate change, many growers are concerned about plants receiving enough cold to be fruitful the next year. Endodormancy, a period of rest, is a term used when plant buds remain dormant due to some internal physiological block, even when external growing conditions are conducive to growth. A chilling requirement is one such physiological block employed by most perennial fruit plants grown in Illinois.

To break endodormancy, the plant must be exposed to a specific number of accumulated chilling hours, roughly in the temperature range between 32°F and 45°F, before growth can resume when favorable conditions occur. So even if it is "shorts weather" outside for us between Christmas and New Year, a dormant apple or peach tree will not break bud if its chilling requirement has not been met.

Nothing in nature is that cut and dry, though. There are also growth-regulating substances that are tied to the chilling requirement. In fact, periods of intermittent warm temperatures require more chilling than continuous cold, suggesting temperatures above optimum subtract from the chill accumulation.

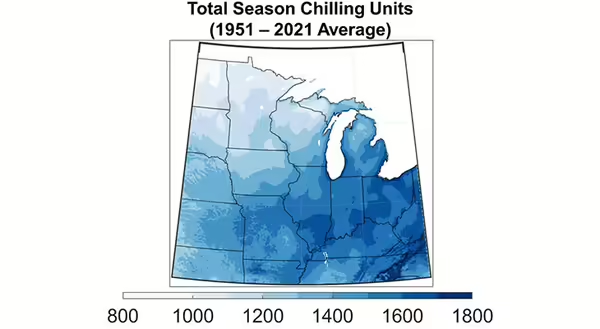

Generally, fruit growers have the most success with species/cultivars that have chilling requirements similar to the chilling typically received at the planting location, so in general low chill (500 hours and less) cultivars for crops like apple, peaches, and blackberry are not suitable to Illinois growing conditions. Illinois historically accumulates 1,100 to 1,700 chill hours per season.

Illinois growers shouldn’t grow low-chill cultivars because of the increased chance of winter kill and crop loss. One example is Prime-Ark® Freedom blackberry. Blackberries, in general, don’t require as much chill as something like an apple, but several cultivars are still suitable for unprotected culture in Southern Illinois. Not so with Prime-Ark® Freedom. It appears to be too low chill for Illinois in unprotected culture. The floricane crop is very early, roughly 7-10 days before Natchez, which sets it up to break bud with the first late winter warmup, sometimes as early as the first or second week of February, way too soon to escape a freeze event, and the reason it is not recommended for unprotected culture in Illinois.

We also have climate change to consider. Dr Trent Ford, Illinois State Climatologist, has developed models to predict changes in chilling hours over the next several decades. For most of us in Illinois, there will be minimal changes in chilling hour accumulation. But for the northern tier counties and above, chilling hours are predicted to increase over the next several decades.

This seems somewhat counter-intuitive, especially when climate change usually means a gradual warmer shift. And that is true in this case as well. Chilling hours don’t usually accumulate below 32°F, so being in the north meant a lot of hours didn’t count because temperatures were too cold. With climate change, winter temperatures are predicted to shift upwards, falling more and more into the temperature range that does count. The concern is plants meeting chilling sooner are more likely to break bud during a late winter warm over the next several decades. It has long been known that fall-applied Ethephon, an ethylene-based plant growth regulator, delays bloom in deciduous fruit species, but not all species and cultivars are as responsive or productive. Further research will be needed to dial in the specifics for each species and cultivar.

The other end of the spectrum is not meeting the chill requirement. This has already been reported in southern states, and according to Dr. Ford’s prediction model, this will only become more and more likely for states south of Illinois. If a plant does not obtain its required chilling hours, it either may not flower at all or will flower much less and, therefore produce a lot less fruit. Again, research will be needed for possible mitigation strategies.

Fortunately, Dr. Ford’s model does not predict Illinois losing chill hours over the next 70 years.