BLOOMINGTON, Ill. – A new invasive species in Illinois should discourage gardeners from sharing divided perennials.

Jumping worms, also called crazy worms or snake worms, are a species of earthworm that depletes nutrients in the soil, and in turn, affect plant growth.

Jumping worms are currently being reported in several counties in Illinois, and continue to spread through the movement of soil, compost, and mulch. This invasive species can spread quickly through dividing and moving perennial plant species.

“Though spring is often the time of plant sales and sharing perennials, this practice can be harmful to private yards and gardens, as well as forested land,” says University of Illinois Extension Horticulture Educator Kelly Allsup. “Jumping worms are similar to earthworms, but with devastating effects.” Depleted soil nutrients, damaged plant roots, changes to soil structure, and even altering the water-holding capacity of soil can be expected from a jumping worm infestation.

They were likely brought stateside via potted plants, landscape material, and other horticultural materials. Although the adults die over winter, they leave behind cocoons with eggs inside that are imperceptibly small. Eggs hatch in spring and reach maturity in 60 days. Though most earthworms in the garden are also non-native and break down organic matter in our forests, jumping worms perform this task at an alarming rate. Illinois first reported jumping worms in 2015, and just four years later they are reported in twenty-three counties and suspected in five more.

Jumping worms swarm in large groups and reproduce in multiple ways. In addition to sexual reproduction, asexual reproduction makes it possible for a single worm to reproduce without a mate. When the population becomes high enough, they become destructive to plant roots in addition to soil.

“Once invasive species populations establish in an area, they can be difficult, costly, or even impossible to eradicate,” says University of Illinois Extension Horticulture Educator Sarah Vogel. “Native plants, animals, forests, waterways, and even native soils can be devastated by non-native and invasive species and their migration. Educational outreach is our best chance at preventing their use and spread.”

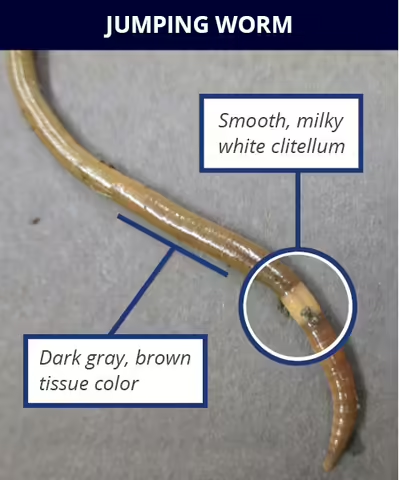

Jumping worms become rigid and actively thrash when disturbed, lending to their name. They may also drop their tail as a defense mechanism. They are 4 to 8-inches long and darker on top than bottom. The key identifying feature on the jumping worm is a smooth, milky white band called the clitellum. The clitellum of a jumping worm is flat and encircles the body; on a common earthworm the clitellum is raised and does not encircle their body, but rather sits like a saddle. This feature is easily seen and helps to easily differentiate it from any other earth worm.

Castings are another good identification technique that can be used during winter. Jumping worms do not usually tunnel in the ground like other earthworms but move through the top two to four inches of leaf litter and top few inches of soil, leaving behind castings that look like coffee grounds. The castings left behind will be uniform as opposed to random-sized piles.

Many gardeners consider worm castings as beneficial to garden soil. However, jumping worms break down organic matter so quickly that nutrients are added at a rate too fast for plant uptake. Since the worms perform this task in the top layer of the soil profile, it can also lead to soil becoming too dry. Depletion of topmost organic matter can also inhibit other beneficial soil microbes in addition to the depletion of nutrients for plant growth.

There is currently no control for jumping worms beyond prevention. Because this species is relatively new to Illinois, accurate counts are difficult due to the species likely being underreported. Most homeowners are unaware of the presence of jumping worms until they actively look for them. How this species will affect nurseries, mulch production, and yard waste collection has yet to be determined.

Stop the spread of jumping worms by following these practices:

- Be aware. In summer, jumping worms are easy to find because they will be above the soil in the leaf layer. If you see earthworms early in the spring, they are not likely jumping worms.

- Investigate your yard or garden. Mix 1/3 cup dry mustard powder with a gallon of water. Remove leaf layer to get to soil surface and pour half of the solution into soil. Jumping worms will come to the surface almost immediately. This practice will not hurt plants.

- Place any adult jumping worms found into a sealed plastic bag then in the trash.

- Clean hiking boots, landscape equipment, and garden tools after each use.

- Do not transfer soils or plants. Most potting soils and organic matter amendments from garden centers are safe and been pasteurized or raised to a temperature that kills the cocoons.

- Discourage plant swaps and plant sales of home-grown plants. Annual plants sales can function by sourcing plants through wholesale nurseries.

- Produce compost on site and ensure it reaches 131 degrees.

- Do not use jumping worms as fishing bait and do not dump your fishing bait.

- Educate yourself and others. Share the University of Illinois Extension Jumping Worms Fact Sheet

- If you suspect jumping worms, please contact the University of Illinois Plant Clinic at plantclinic@illinois.edu or 217-333-0519. Include an image for identification.

SOURCE: Kelly Allsup, Horticulture Educator, Livingston, McLean, and Woodford Counties.

ABOUT EXTENSION: Illinois Extension leads public outreach for University of Illinois by translating research into action plans that allow Illinois families, businesses, and community leaders to solve problems, make informed decisions, and adapt to changes and opportunities.