This year has been good for many plants, but not all. In late spring Central Illinois went through almost three weeks where it rained at least once per day. Many of our plants responded to this favorably. Standing in a pollinator garden a few days ago, the goldenrod towered over me. Our vegetable gardens have seldom needed a drink from the hose. Even the grass has remained mostly green and actively growing.

Yet as the early rain brought with it a bounty of flowers and fruit, there are also some disease problems. This year a very common problem has been the dieback of lilac shrubs.

Lilacs welcome spring with their sweet-scented flowers and blooms that range from white to pink to purple. Lilac does little else except prepare for next year’s flower show for the rest of the year. Even though lilac performs only once a year, they are still great shrubs used throughout the landscape.

Common lilac problems in the summer

There are common problems that routinely plague lilac. Powdery mildew can be expected on most older lilacs during the summer. This fungal disease creates a powdery coating on the leaves, resulting from dry periods with several days of high humidity. During a wet year, powdery mildew is often not a culprit as the white film often can be washed away once rains become more regular.

Another pest is the lilac stem borer. This is a clearwing moth that lays her eggs at the base of the lilac and the larva bores into the stem. These moths often only target stressed lilacs or very old stems. Signs include sawdust, sap, and frass near the base of the plant. Yet the samples that have come into the Extension office do not indicate lilac borer.

Leaf scorch may also be an issue many lilacs are experiencing this year. Saturated soils caused by excessive rains can effectively suffocate and kill portions of the root system. Once the hot, dry summer weather arrives, the plant doesn't have a root system capable of supporting the vegetation. Leaves will often quickly dry up and remain suspended on the plant.

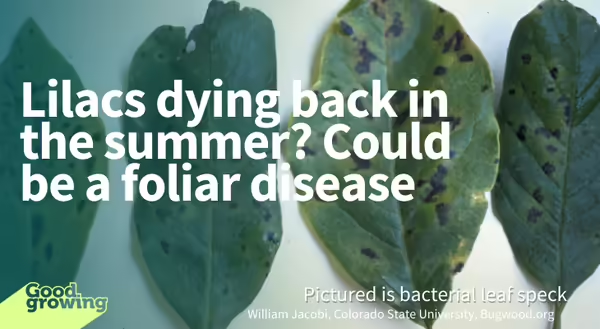

The true culprit(s) may not even be present anymore. It appears during our stretch of cool rainy weather, a bacterial or fungal disease was able to spread rapidly in lilac plantings. Now that our weather has warmed and dried out, these diseases can no longer be active in the summer heat. Yet, the damage is done. What began with spots on leaves has progressed to leaves completely turning brown and branches dying back.

Another weather event that could have created the perfect storm for lilac foliar disease is a hard freeze in the spring in Central Illinois this year. Late spring frosts can damage tender leaf tissues allowing infection from leaf pathogens. Symptoms may not be apparent until later in the season, when summer heat puts additional stress on the plant.

However, while I am fairly confident a foliar disease is a cause I have yet to see a lab test confirming these diseases. The two following pathogens are both likely contenders.

Many of the disease signs on lilac I’ve seen this season point to a fungal pathogen Pseudocercospora leaf spot. Additionally, a disease that causes very similar symptoms is the bacteria Pseudomonas spp. While these two pathogens create similar problems in lilac, it is important to distinguish one is a fungus and the other a bacteria. So how do you tell the difference between the two? The answer requires a lab test from a plant diagnostic lab like the University of Illinois Plant Clinic. Anything else is just guessing. This could be wasteful, for instance, if you decide to spray a bacteria with a fungicide.

What can be done?

Yet, all hope is not lost. Many of these lilacs will recover next year even though flowering may be affected.

A common thread with most affected lilac samples I’ve received is that they were older varieties, poorly pruned, or not pruned at all. Pruning is critical to reducing disease opportunities in multi-stemmed shrubs like lilac. When it comes to pruning lilacs, put the hedge shears down. Instead, reach for loppers or a handsaw and remove a third of the thickest (oldest) stems at the base of the shrub, near the ground. This is called renewal pruning and can be done annually or every few years. Renewal pruning opens up the shrub, promotes better airflow, and gives younger growth the room to develop and put on a great flower show.

If a lab test confirms you're dealing with the fungal Pseudocercospora leaf spot, monitor next spring for the disease. We may not encounter the conditions that favor foliar diseases, which would save you from spraying. Should the lilac display symptoms products containing copper sulfate, sulfur, tebuconazole, or triticonazole would limit the spread of the disease.

Much of the advice in the above paragraph rings true for the bacterial disease Pseudomonas spp. However, for chemical control, the active ingredient copper octanoate is recommended.

If the disease reoccurs every year, it may be more cost-effective to replace the lilac with a newer variety that has been bred to resist these common diseases.

Good Growing Tip of the Week: Before you reach for the fungicide to stop the disease, make sure the disease is still active. For instance, spraying for lilac leaf spot now (August) wouldn’t control the disease as the fungus is not currently active. Spray when the disease is active, in the case of our lilacs typically in late spring when the disease first appears.

Want to get notified when new Good Growing posts are available? SIGN ME UP!

Meet the Author

Chris Enroth is a horticulture educator with University of Illinois Extension, serving Henderson, McDonough, Knox, and Warren counties since 2012. Chris provides horticulture programming with an emphasis on the home gardener, landscape maintenance personnel, and commercial landscapers.

Additional responsibilities include coordinating local county Master Gardener and Master Naturalist volunteers - providing their training, continuing education, advanced training, seasonal events, and organizing community outreach programs for horticulture and conservation assistance/education.

In his spare time, Chris enjoys the outdoors, lounging in the garden among the flowers (weeds to most).