The long wait is finally over! After spending 13 (or 17, depending on where you’re at) years underground feeding from roots, periodical cicadas have started to emerge (at least in central and southern Illinois). Soon, many places will be awash in cicadas.

While this mass emergence may seem overwhelming or disgusting to some, it is important to remember that periodical cicadas are not poisonous or venomous, nor do they bite or sting, and don’t pose a threat to humans or animals. So, what can we expect now that they are beginning to emerge?

Which trees do they ‘attack’?

Periodical cicadas are generalists when it comes to egg-laying. They’ll lay their eggs in just about any woody plant that is the right size (around the size of a pencil, up to 0.5 inches in diameter). That being said, they do have some plants that they prefer to lay their eggs in, like oak, maple, hickory, apple, birch, dogwood, linden, willow, elm, ginkgo, and pears. They tend to avoid plants that produce a lot of sap or gum, like conifers, cherries, peaches, and plums, because this could prevent eggs from hatching and nymphs from reaching the ground.

If you have trees or shrubs you are concerned about, they can be covered with netting that has holes that are ¼ inch or smaller. Egg laying usually begins 7-10 days after male cicadas start singing.

Why am I seeing cicada holes in my yard but no cicadas?

Periodical cicadas will begin digging holes to the surface a few weeks before they emerge from the ground. They'll wait underground until soil temperatures, 7 to 8 inches deep, are consistently around 64 degrees Fahrenheit, at which point, they'll emerge and molt into adults.

Not sure what your soil temperatures are like? Check out the Illinois Natural History Survey’s Water and Atmospheric Resources Monitoring Program (WARM). There you can find soil temperatures across the state.

Another possibility is that cicadas have begun emerging, but you don’t have large numbers emerging yet. When they emerge, cicadas will climb up objects to molt, and they could be higher up in trees than you are looking.

Are the white cicadas a different species or are males and females different colors?

If you’ve gone out early in the morning (or in the evening), you may have noticed white cicadas. These aren’t different species of cicada but rather newly molted adults that have not yet hardened. Over time, these white adults (teneral) will darken and harden into the more recognizable black and orange.

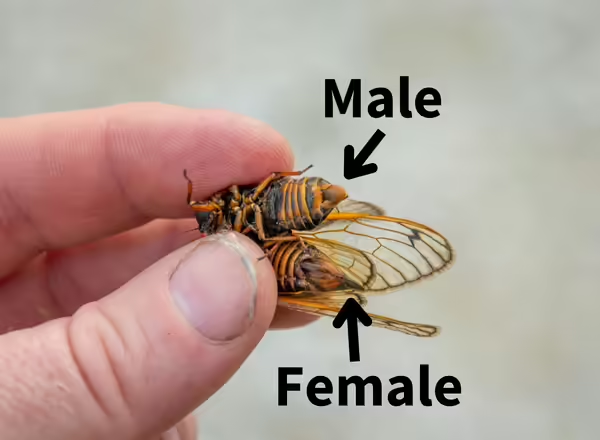

Both male and female periodical cicadas have black bodies and orange wings. If you want to tell the difference between males and females, look at the undersides of their abdomens. Female abdomens come to a point, and they have an ovipositor, while males’ abdomens are more blunt.

I’ve been seeing cicadas that didn’t make it out of their shell or have deformed wings. Why is that?

If you’re out looking for cicadas, you’ll likely encounter some individuals who had a molting failure/accident. There are a variety of reasons this can happen, such as molting cicadas being knocked to the ground by wind or pesticide use. Another common reason, particularly in suburban areas, is overcrowding.

In many suburban landscapes, the tree canopy is relatively open, which is attractive to cicadas (they like laying eggs on branches exposed to sun). This leads to large concentrations of eggs being laid on solitary trees. When all these cicadas emerge, it can lead to overcrowding, and emerging cicadas can be damaged when other cicadas crawl over them or knock them off their perch. In a study conducted in Illinois, over 30% of cicadas emerging in a suburban yard were killed while trying to molt due to high populations/crowding. So, it is possible to have too much of a good thing when it comes to periodical cicadas.

How loud is it really going to be?

Males will typically begin singing 5-6 days after they emerge, and how loud it gets will largely depend on the number of cicadas you have in your area. Male cicadas will group together and form chorus centers where they will begin to call for females (each species has a distinctive song). The more males present in those centers, the louder it will be. This calling can reach over 90 decibels (dBA), which is as loud as a lawnmower, motorcycle, or tractor. So, if you’re seeing a lot of cicadas, there’s a good chance it’s going to get loud.

What’s the point of cicadas, do they do anything good, or are they just here to destroy our trees and scream at us?

Many people often wonder what the point of cicadas is or what they are good for. One could argue what’s the point of any organism. But philosophical questions aside, periodical cicadas are beneficial to our ecosystems in a number of ways.

- As they dig their tunnels to the surface, they help aerate the soil and improve water infiltration into the ground.

- Their egg-laying can provide some natural pruning to trees. This pruning can lead to a flush of growth and increased flowering and fruit production the following year.

- When cicadas die and begin to decompose, they release nutrients into the soil, particularly nitrogen. This natural fertilizer can lead to increased growth of plants and an increase in soil microbes. Studies have found that sycamore trees grew 10% more than trees that were not fertilized by dead cicadas, and American bellflowers grew 61% larger and produced seeds that were 9% larger than unfertilized plants.

- Periodical cicadas will serve as a food source for a wide range of animals. A variety of birds, including grackles, robins, blue jays, red-winged blackbirds, sparrows, and woodpeckers, will feed on them. In emergence years, birds will often have more offspring, and more of them will survive.

Mammals like squirrels, raccoons, and skunks, as well as cats and dogs, will readily feed on periodical cicadas. Even insects, such as ants, will get in on the action.

Want more information on periodical cicadas check out our previous blog post on them: The cicadas are coming! Periodical cicadas in Illinois in 2024.

Good Growing Fact of the week: People can also eat periodical cicadas, with a few caveats. If you are allergic to shellfish, you should avoid eating cicadas. Be careful about where you harvest; they can accumulate heavy metals, and avoid areas with heavy pesticide use. Also, make sure you cook them before eating them. If you want to learn more, check out the May 24 episode of the Good Growing Podcast!

Bonus Fact of the Week: Animals that feed on cicadas aren’t the only ones that benefit from their presence. A study that was done during Brood X emergence in 2021 found that birds shifted their diets to cicadas from their normal diet of caterpillars. This led to an increase in caterpillar populations, although it also led to an increase in feeding damage caused by caterpillars to oak trees.

Resources and for more information

Cooley, John R, and Greg Holmes. 2023. “Periodical Cicadas (Magicicada Spp.): Predator Satiation, or Too Much of a Good Thing?” Great Lakes Entomologist 56 (1). https://doi.org/10.22543/0090-0222.2448.

Getman‐Pickering, Zoe L, Grace J Soltis, Sarah Shamash, Daniel S Gruner, Martha R Weiss, and John T Lill. 2023. “Periodical Cicadas Disrupt Trophic Dynamics through Community-Level Shifts in Avian Foraging.” Science 382 (6668): 320–24. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adi7426.

Simon, Chris, John R. Cooley, Richard Karban, and Teiji Sota. 2022. “Advances in the Evolution and Ecology of 13- and 17-Year Periodical Cicadas.” Annual Review of Entomology 67 (1): 457–82. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-072121-061108.

White, JoAnn, Monte Lloyd, and Jerrold H. Zar. 1979. “Faulty Eclosion in Crowded Suburban Periodical Cicadas: Populations out of Control.” Ecology 60 (2): 305–15. https://doi.org/10.2307/1937659.

Williams, K S, and C Simon. 1995. “The Ecology, Behavior, and Evolution of Periodical Cicadas.” Annual Review of Entomology 40 (1): 269–95. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.40.010195.001413.

Yang, Louie H. 2004. “Periodical Cicadas as Resource Pulses in North American Forests.” Science 306 (5701): 1565–67. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1103114.

Yang, Louie H., and Richard Karban. 2019. “The Effects of Pulsed Fertilization and Chronic Herbivory by Periodical Cicadas on Tree Growth.” Ecology, April, e02705. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2705.

Want to get notified when new Good Growing posts are available? SIGN ME UP!

Give us feedback! How helpful was this information (click one): Very helpful | Somewhat helpful | Not very helpful

MEET THE AUTHOR

Ken Johnson is a Horticulture Educator with University of Illinois Extension, serving Calhoun, Cass, Greene, Morgan, and Scott counties since 2013. Ken provides horticulture programming with an emphasis on fruit and vegetable production, pest management, and beneficial insects. Through his programming, he aims to increase backyard food production and foster a greater appreciation of insects.